HMS Birkenhead and the Embers of Virtue

You have almost certainly never heard of Margaret Seton. Her name doesn’t appear in any history books. She now rests in a grave in her native Scotland. But if you find yourself walking among the silent sleepers of Greyfriars Kirkyard, perhaps you might look for an epitaph—now worn smooth—and thank the woman who helped to save the lives of seven women and thirteen children when disaster suddenly struck one summer’s night, February 26, 1852.

Saving so many lives is remarkable for anyone. Perhaps what is even more remarkable is the fact that Margaret, or Peggy as she was known, had passed away in 1788—64 years earlier.

On February 25, 1852, the HMS Birkenhead, a 210 foot iron-hulled ship set out from Simon’s Bay, near Cape Town, South Africa. It carried 643 souls. Sailors, soldiers, and some of their wives and children. Its destination: Port Elizabeth. A destination it would never reach.

The commanding officer on board that fateful night was one Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Seton of the 74th Highlanders. Margaret was his grandmother. And she, and her grandson, were about to change naval history.

Margaret was only 39 when she died. If we can still make out the words of her epitaph, etched by her husband, we would read: “Sacred to the memory of Margaret Seton who never intentionally gave pain to any living creature. Her judgment was sound, her perceptions clear, her taste refined, her integrity incorruptible, her beneficence unlimited. Had fortune placed her in a high rank in this world, the elegance of her manners would have graced, her virtues adorned, and her mental qualities added lustre to the most exalted station.”

Note that her husband doesn’t claim that she was merely worthy of the highest station. On the contrary, he asserts that the highest stations themselves would have received additional beauty and dignity simply by the fact that she held them.

The epitaph continues, “Human misery, in whatever shape it appeared, was sure to attract her tenderest regard. On these occasions, forgetting herself, she only thought of the distress of others.”

“She only thought of the distress of others.”

How often did Alexander Seton repeat those words to himself?

The Cape of Good Hope was originally named, “the Cape of Storms.” Ironically, on the night of February 26th, the waters off the Cape were quite calm and flat, which was why the sailors on board never spotted the uncharted hidden rock that lay just below the waveless sea that night.

The razor sharp rock acted as a can opener to the ship’s metal hull. The lower compartment was flooded within moments. Hundreds of sleeping soldiers in the lower deck awoke for a few brief moments—for the final time.

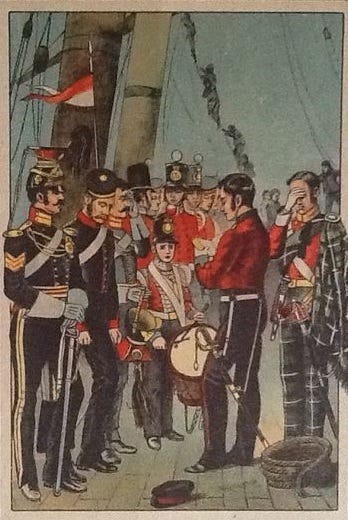

On deck, Colonel Seton immediately ordered his men to fall in to each side of the deck. Then, he quickly conveyed to his officers that they must keep discipline among the men. No small number of these soldiers were untried in battle, their fortitude yet untested, their virtue yet unknown.

It would be tested that night, and it would be made known the world over.

Ensign Lucas wrote of that night that, “Almost every body kept silent, indeed nothing was heard, but the kicking of the horses and the orders of [the ship’s captain] Salmon, all given in a clear firm voice.”

All the women and children were loaded into the ship’s cutter, with Colonel Seton, sword in hand, at the gangway keeping the way clear for the women and children, and preserving good order in his men. Beyond the cutter, only two other smaller boats were able to be used. This left hundreds of men still aboard.

The engine room now being flooded, the ship’s engines continued to turn with no way of stopping them. This would propel the ship once again into the hidden rock below. It would be the ship’s final death blow.

She broke in two. It was only ten minutes from the time she first struck the submerged rock.

She would be fully submerged in ten minutes more. The ship’s captain ordered that everyone should jump overboard and make for the three ships.

Colonel Seton however had realized what the ship’s captain seemingly had not: 400 men frantically swimming for 3 small boats would almost certainly endanger the lives of the women and children on board the boats.

And so, Alexander Seton gave one final order.

“The whole tenor of her life was one continued act of beneficence…Reader, from this example learn, that it is neither wealth nor high rank, but the virtues of the heart alone that tend to promote the happiness, and insure the esteem of mankind: If these are blessings of which thou art emulous, cherish the seeds of beneficence in thy mind, and cultivate the social affections, in the full assurance that thou shalt certainly obtain the prize if you faint not, nor ever weary in the course.”

Alexander Seton, Esquire, of the house of Mounie was born in 1814. For his first fifteen years, he was educated at home. By all accounts, we can conclude that Seton was almost certainly a genius. He studied advanced mathematics and chemistry, and even went abroad to Italy for two years in order to pursue these subjects with more rigor under a renowned professor.

He was greatly moved by art, literature, and poetry, and excelled in these as well. We are told that “had he been induced to publish his literary labors, these would have established his reputation as a writer and a poet.” He sketched, painted, and was an accomplished musician. He loved the beauty of the earth, so in addition to chemistry, he also excelled in geology and botany.

To all this, perhaps what is most astounding was his incredible facility for language. We have it on good authority that he was the master of no less than fifteen different languages. By the time he was a teenager, he had already shown himself to be greater than his Latin, Greek, and French tutors. He picked up languages whenever he traveled, so that he became fluent in Italian, Persian, Hindi, Sanskrit, and Hebrew, among many others.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Alexander Seton was one of the most accomplished men in the British Empire. More important than this, though, his friends wrote of him, “His whole life was a brilliant example of that true Christianity which softens, while it elevates the mind and heart of those under its influence.”

His friends further tell us that “To his Mother he ever displayed the most devoted attachment…no amount of duty prevented regular correspondence.”

It would be no fancy of imagination to suppose that Seton then thought of his mother Janet, and his grandmother Peggy, and once again returned to the words on the epitaph. “Reader, from this example learn, that it is neither wealth nor high rank, but the virtues of the heart alone…thou shalt certainly obtain the prize if you faint not, nor ever weary in the course.”

And so, with sword in hand, Seton gave his final order: stand fast.

With the ship sinking below them, with sharks swirling around them, with the emergency boats rowing away from them, to the soldiers and sailors everlasting glory, they stood fast.

One of the soldier’s would later remark: “The order and regularity that prevailed on board, from the moment the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I had thought could be effected by the best discipline; and it is the more to be wondered at seeing that most of the soldiers were but a short time in the service. Everyone did as he was directed and there was not a murmur or cry amongst them until the ship made her final plunge – all received their orders and carried them out as if they were embarking instead of going to the bottom – I never saw any embarkation conducted with so little noise or confusion.”

This night, on this ship, the law of the sea “Women and children first” was born. It has been said that the laws of the sea are written in blood. It was always the case though that these are laws written after a tragedy, by other men, in order to protect ships in the future. Not so on this night. These men wrote the law, “Women and children first” with their own blood, as their final, heroic act.

They stood fast.

Just before the ship finally plunged beneath the waves, one of Seton’s men shook hands with him and said, “I hope we shall meet ashore.” The man relates that, while giving his answer, Seton was “As cool and collected…as if he had been on parade.” Seton answered him, “I am afraid not, for I cannot swim.”

Many men were quickly taken by the sharks. Yet, such was their fortitude that even then they followed Colonel Seton’s final order as they refused to swim too close to the lifeboats.

Ensign Alexander Russell, who was piloting the boat containing the women and children was urged by one family to pick up their father who they could see in the water. Even so, the man refused to approach the boat. Ensign Russell, taking pity on the poor suffering family, jumped into the water to help the father aboard. Russell was well aware that the small boat was already at capacity. When he jumped into the water, he did so knowing full well that he must trade places with the father. Not five minutes later, Ensign Russell was dragged beneath the waters by a great white.

Alexander Russell was just 19 years old.

When morning dawned, of the 643 souls on board the ship, only 193 had survived.

Every woman and child on board the ship survived.

Every one.

One month later, the Morning Herald would write, “We venture to assert that the whole annals of Naval disaster afford no nobler instance of coolness, true courage, and steady discipline than was exhibited by the ill-fated [Colonel] Seton, and the officers and soldiers under his command. We defy the whole history of our race to produce a more striking instance of bravery and coolness than is here exhibited.”

In a very real sense, every man’s character is formed by the generations that come before him. Selflessness, courage, compassion, and charity are embers that must be passed from generation to generation. The world is set ablaze when others come into contact with these embers. This is certainly true of Margaret Seton. The words of George Eliot undoubtedly apply to her, “But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

These embers formed Alexander Seton. “She only thought of the distress of others.” He in turn passed them to every man that fateful night. The embers traveled even to Prussia, whose king “caused the splendid story of 'iron discipline and perfect duty' to be read aloud at the head of every regiment in his service.”

“Women and children first” is informally known as “The Birkenhead drill.” Poets such as Rudyard Kipling, and Francis Doyle immortalized it in poetry. The latter concludes his poem:

They sleep as well, beneath that purple tide,

As others, under turf; —

They sleep as well, and, roused from their wild grave,

Wearing their wounds like stars, shall rise again,

Joint-heirs with Christ, because they bled to save

His weak ones, not in vain.

If that day's work no clasp or medal mark,

If each proud heart no cross of bronze may press,

Nor cannon thunder loud from Tower and Park,

This feel we, none the less:

That those whom God's high grace there saved from ill —

Those also, left His martyrs in the bay —

Though not by siege, though not in battle, still

Full well had earned their pay.We may well think Doyle right in his sentiment. For, while we do not know the last thing that Colonel Alexander Seton ever beheld in this life, we may, perhaps, look to his grandmother’s epitaph one final time. There, we may find a clue, not of what he saw last, but of what he saw first.

The final two lines of the epitaph read: “Blessed are the pure in spirit, for they shall see God. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.”