Repaid in full: 9/11 and the people of Halifax

Twenty years ago, September 11, 2001, amid the the suffering and chaos that was unleashed that day, something else emerged—a torrential outpouring of kindness and charity. To the widowed. To the injured. To the wayfarers. No one expected anything in return. They acted simply because they saw a fellow soul—wounded—and in need of the balm of human kindness.

No, they didn’t expect anything in return. And yet, kindness finds a way to repay kindness. Like begets like. Love begets love. Kindness begets kindness. The cynical scoff at the notion. They demand immediate proof that a kindness done to a fellow man redounds back to them. But this is not the way of grace. Sometimes, that kindness will be repaid months, years, even decades later. When we most need it. When we ourselves may have forgotten that kindness, once rendered, so long ago now.

Yes, sometimes it takes decades. On Sept 11, 2001, a kindness was repaid—84 years in the making.

On the morning of December 6, 1917, in Halifax Nova Scotia, the SS Mont-Blanc set sail. Its cargo: TNT, along with highly flammable chemicals. At the same time, the SS Imo was passing along the same narrow strait as Mont-Blanc. The Captain of the Mont-Blanc, Francis Mackey, saw the Imo around 1 kilometer away, coming toward him in a way that would indicate that Imo would cut off Mont-Blanc. He blasted his whistle to warn Imo. The Imo blasted back two whistles to indicate that it had the right of way and would not give way. Mackey, realizing that they were in real danger now, immediately cut his engines, turned starboard, and again blasted his whistle hoping that the Imo would likewise turn hard starboard. On board the Imo, Captain Haakon From was struggling with his ship. It was travelling without cargo which made it difficult to maneuver — especially in a narrow corridor which it now found itself. Captain From replied with two whistle blasts.

The ships collided around 8:46am.

At 8:46am, decades later, a plane would crash into the World Trade Center.

A fire immediately started on board the Mont-Blanc. Horrifyingly, the collision sent the ship straight into the harbor pier, which itself caught fire. Onlookers gaped at the ship and pier ablaze. Firefighters were almost immediately on the scene.

Then, word spread what the cargo was on board the ship: almost 6 million pounds of explosives.

Nearby train dispatcher, Vince Coleman heard what the cargo was, and ran. He ran as fast as he could. Only, he didn’t run like his life depended on it. He ran like other lives did. Vince Coleman didn’t run away from the pier to try to save himself. He ran back to the railway station, which was just a few hundred feet from the pier. He knew exactly what he was doing--there was a train coming and he needed to warn them--he knew exactly what he was doing.

Vince Coleman ran.

There may not be anyone else in history whose last words we have by way of Morse Code.

We have Vince Coleman’s.

“Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye, boys.”

They received the message just 4 miles from the station. 300 people survived that day because of his message.

At 9:04am, the Mont-Blanc exploded.

The shockwave shattered windows over 50 miles away. A crew off the coast of Massachusetts heard the blast, some 300 miles away. The force caused a tsunami. The ship’s anchor, weighing 1100 pounds, flew over the entire city of Halifax, landing two miles away. Not a single structure within a 1.6 mile radius survived.

Everything was gone.

And what felt like everyone.

1,600 souls immediately lost their lives. 9,000 men, women, and children suffered terrible injuries. Bodies were literally thrown onto overhead telegraph wires. Fires burned throughout Halifax in the buildings that were not completely destroyed. And now the survivors were without anyone to help them and no place to go.

December, in the brutal Halifax winter, and the survivors had no place to go. 25,000 men, women, and children needed help. And they needed it now.

“So then, as we have opportunity, let us do good to all men…”

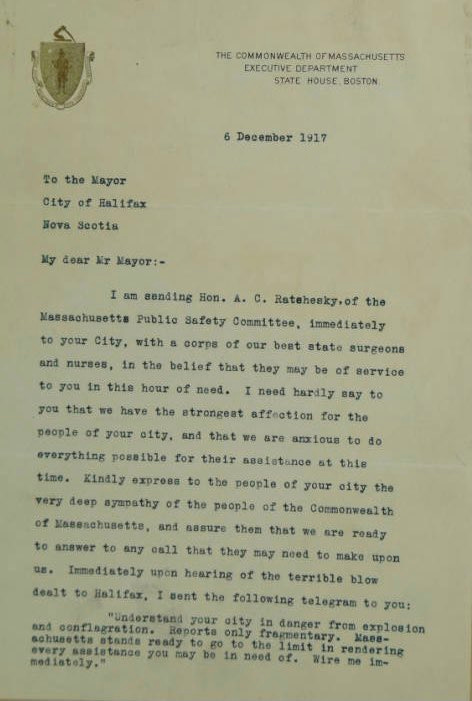

In Boston, on that day, word reached the Governor, Samuel McCall. What he wrote is one of the great letters of American History, and should be taught to every schoolchild.

My dear Mr. Mayor: I am sending Hon. A. C. Ratshesky, of the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee, immediately to your city, with a corps of our best state surgeons and nurses, in the belief that they may be of service to you in this hour of need. I need hardly say to you that we have the strongest affection for the people of your city, and that we are anxious to do everything possible for their assistance at this time. Kindly express to the people of your city the very deep sympathy of the people of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and assure them that we are ready to answer to any call that they may need to make upon us. Immediately upon hearing of the terrible blow dealt to Halifax, I sent the following telegram to you:

“Understand your city in danger from explosion and conflagration. Reports only fragmentary. Massachusetts stands ready to go to the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of. Wire me immediately.”

Upon being informed that the wires were out of commission, through the good offices of the Federal Government at Washington, this further telegram was sent to you by wireless:

“Since sending my telegram this morning offering unlimited assistance, an important meeting of the citizens has been held and Massachusetts stands ready to offer aid in any way you can avail yourself of it. We are prepared to send forward immediately a special train with surgeons, nurses, and other medical assistance, but await advices from you.”

Won’t you please call upon Mr. Ratshesky for every help that you need. The commonwealth of Massachusetts will stand back of Mr. Ratshesky in every way.

Respectfully yours,

Samuel W. McCall, Governor

P.S. Realizing that time is of the utmost importance, we have not waited for your answer, but have dispatched the train.

The train left Boston less than 12 hours after the explosion.

“Massachusetts stands ready to go to the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of…”

When a Halifax representative received the letter, and read those words of the Massachusetts Governor, he openly wept and proclaimed, “Just like the people of good old Massachusetts. I am proud of them.”

The governor immediately created the Massachusetts Halifax Relief Committee, which sent out a message to the citizens of Boston, “Generous contributions will be needed to carry on the work of relieving immediate distress by providing clothes, food, medicines and material for the temporary housing of the homeless and suffering…Later will come the great work of rehabilitation to which we are all committed as near neighbors of the stricken city. Cash will be required to do all this, and Massachusetts may be called upon for a million dollars. Everybody is asked to subscribe generously and as quickly as possible.”

Millions of dollars in cargo left Boston on the first ship: mattresses, food, clothing, medical supplies. The Boston Symphony Orchestra held a benefit concert.

The Americans built shelters for the homeless. Fed the hungry. Gave drink to the thirsty. Clothed those who had none. And buried the dead.

The members of the Maine National Guard rebuilt a badly damaged building into a field hospital with 200 beds. In less than a day.

Millions of dollars were given, overnight, by ordinary American citizens. Hundreds of American doctors, nurses, and engineers came to help. They stayed for months and in some cases years.

The following Christmas, 1918, Boston received the most beautiful Christmas tree anyone had ever seen. Standing 50 feet tall, it was a gift from the people of Halifax to the people of Boston.

A gift from one friend to another.

And since 1971 the people of Nova Scotia have sent a Christmas tree to the citizens of Boston. To say thank you. To say we remember. To imagine that this is simply a small gesture of little meaning would be to dramatically underestimate its importance to the people of Halifax. It has been said of the tree that "people have cried over it, argued about it, even penned song lyrics in its honor." The tree is of immense pride to those residents and they willingly offer some of the most beautiful trees in the country — one their grandfather may have planted — to be given as a token of the deep abiding affection they hold for the people of America, and especially Bostonians. It was their way of saying, “Perhaps we can never fully repay you for your kindness, but this is our way of remembering it.”

Remembering that kindness had gone on, unabated, until the morning of September 11, 2001.

At 9:04am, 84 years earlier, the Mont-Blanc exploded and the people of Boston came to help. At 9:04am, 84 years later, 1 minute after a second plane, taking off from Boston, hit the World Trade Center, Boston Air Route Traffic Control Center stopped all departures from airports in its jurisdiction. Soon after, air traffic across the entire United States was shut down. For the first time in history. Every plane needed to land as soon as possible.

At 11:35am, a United Airlines Boeing 767 landed at Halifax Stanfield International Airport. It was the first of the day. It wouldn’t be the last. They would receive 40 diverted flights—more than any other airport in the world. Halifax. Population 350,000. On board those 40 flights were 8,000 passengers, mainly Americans, reeling from the attack on their homeland, wondering if their loved ones were safe. Stranded away from their home.

“Massachusetts stands ready to go to the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of.”

Perhaps the people of Halifax remembered those words on that morning. What we do know is what the people of Halifax did. They went to the limit in rendering any assistance these wayfarers needed. Many opened their own homes to those in need of a bed or shower.

Joyce Carter, the CEO of Halifax Airport said, “I remember, in the midst of the tragedy and devastation of the day, how very proud I was to witness my colleagues stop everything and team together to focus entirely on the needs of the thousands of people who arrived unexpectedly on our doorstep. It took five days before flights started moving again and during that time members of our airport community along with so many Nova Scotians opened their hearts and their homes to these unexpected visitors.”

In December, 2001, a Christmas tree arrived in Boston Common. Just like it always had. It was a thank you from one friend to another. It was their way of saying, “Perhaps we can never fully repay you for your kindness, but this is our way of remembering it.”

But that Christmas, when the residents of Halifax were carrying out their Christmas shopping, they saw their own thank you. They knew Americans considered their kindness repaid in full. There, in downtown Halifax, on a giant billboard, a thank you message, from the passengers that spent 5 days in the hearts and homes of the citizens of Halifax. A gift from Americans to the people of Halifax.

A gift from one friend to another. A kindness repaid. In full.

I've read this story before at least twice and yet again today .... I can never get enough of this story.

-- A beautiful story of the Love of 2 Cities/Nations when Catastrophe hits ...

--- My wife and I visited Halifax and all of Southwest bay area once .... I even stood on my Great Grandpa Guilbeaux's burial site ...

--- The people of Halifax and all of Nova Scotia are the Kindest people and welcome people from the US with Open Arms ...

--- They also helped in the Catastrophic Titanic Sinking off the Shore of Halifax ...

--- This is a Great Read !!! Thanks for posting ...

A lovely article that juxtaposes beautifully two kindnesses rendered. As a lifelong resident of Halifax and a tour guide, I take great pride in recounting the kindnesses of our American friends particularly when my tour goes by Massachusetts Avenue in the north end of our city not far from our Ground Zero (Pier 6). As for 9/11, many lifelong friendships were established as many Haligonians opened their homes to stranded travelers. (Note: Francis Mackey was the local harbour pilot that morning. The captain of the Mont Blanc was Amédé LeMédec.)